About CommentOnThis.com

This is a site designed to make it easier to take the core of large published reports and allow anyone to comment on them.

More...

Contents:

- Defamation and the internet: the multiple publication rule

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- The civil law on defamation

- Background

- The multiple publication rule and the limitation period

- Extending qualified privilege to material on online archives in certain circumstances

- Interaction with the limitation period for defamation actions

- Key issues for consideration

- Conclusion

- Questionnaire

- Appendixes

- Cost Benefit Analysis

- BASE CASE (“do nothing”) Description

- OPTION 1

- OPTION 2

- OPTION 3

- 4. Competition Assessment

- 5. Small Firms Impact Assessment

- 6. Legal Aid and Justice Impact Test

- 7. Race, Disability and Gender Assessment

- 8. Human Rights

- The consultation criteria

Defamation and the internet: the multiple publication rule

Consultation Paper CP20/09

A consultation produced by the Ministry of Justice.

Published on 16 September 2009 This consultation will end on 16 December 2009

This information is also available on the Ministry of Justice website: www.justice.gov.uk

Executive summary

The multiple publication rule and the limitation period

This consultation paper considers the arguments for and against the multiple publication rule (which provides that each publication of defamatory material can form the basis of a new cause of action) and the alternative of a single publication rule which would permit only one action to be brought in England and Wales against particular defamatory material. It seeks views in principle on whether the multiple publication rule should be retained or a single publication rule introduced and on how a single publication rule might work in practice.

The paper also considers in that context what limitation period for defamation actions would be appropriate in the light of the Law Commission’s recommendation in its report on Limitation of Actions that the limitation period should be changed from the current period of one year from the date of publication of the allegedly defamatory material to three years from the date of knowledge of the allegedly defamatory material, with a ten year long-stop from the date of publication.

It is proposed that if the multiple publication rule were retained, the limitation period should not be extended from the current period of one year from the date of publication (with discretion to extend). It is suggested that, if a single publication rule were to be introduced, the arguments for extending the limitation period beyond one year are not strong, but seeks views on whether a ‘date of publication’ or ‘date of knowledge’ approach should be used, and whether the latter should be accompanied by a ten year long-stop from the date of publication.

An alternative approach is also considered of extending the defence of qualified privilege to publications on online archives outside the one year limitation period for the initial publication, unless the publisher refuses or neglects to update the electronic version, on request, with a reasonable letter or statement by the claimant by way of explanation or contradiction.

Introduction

This paper sets out for consultation the issue of whether there is a need for reform of the law in relation to the multiple publication rule in defamation proceedings and the limitation periods for civil actions. The consultation is aimed at parties involved in actions for defamation and their representatives and at others with an interest in the law on defamation in England and Wales.

This consultation is being conducted in line with the Code of Practice on Consultation issued by the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills and falls within the scope of the Code. The Consultation Criteria, which are set out on page 44, have been followed.

An Initial Impact Assessment on the issue discussed in this consultation paper is attached at page 31. The Impact Assessment indicates that the issues under consideration are likely in particular to affect media and publishing companies; members of the public and organisations subject to defamatory allegations; legal professionals representing both claimants and defendants; and the courts in dealing with defamation proceedings. The issue is likely to lead to some costs or savings for businesses.

Comments on the Impact Assessment and the specific questions that they contain are particularly welcome.

Copies of the consultation paper are being sent to:

- The Senior Judiciary through the Judicial Office of England and Wales

- Council of Her Majesty’s Circuit Judges

- Association of Her Majesty’s District Judges

- Civil Justice Council

- Law Society

- Law Reform Committee of the Bar Council

- Institute of Legal Executives

- Association of British Insurers

- Confederation of British Industry

- Trades Union Congress

- Citizens Advice

- Forum of Insurance Lawyers

- Newspaper Society

- Publishers Association

- Society of Editors

- The Press Association

- English PEN

- Internet Service Providers Association

- Ofcom

- Solicitors, media companies and others who have expressed an interest or responded to previous consultations in this area

- Press Complaints Commission

- Better Regulation Commission

- Equality and Human Rights Commission

However, this list is not meant to be exhaustive or exclusive and responses are welcomed from anyone with an interest in or views on the subjects covered by this paper.

The civil law on defamation

Background

The civil law on defamation has developed through the common law over hundreds of years, periodically being supplemented by statute, most recently by the Defamation Acts of 1952 and 1996.

Defamation is the collective term for libel and slander, and occurs when a person communicates material to a third party, in words or any other form, containing an untrue imputation against the reputation of the claimant. Material is libellous where it is communicated in a permanent form, or broadcast, or forms part of a theatrical performance. If the material is spoken or takes some other transient form, then it is classed as slander.

Whether material is defamatory is a matter for the courts to determine. The main tests established by the courts in deciding whether material is defamatory are whether the words used “tend to lower the plaintiff [claimant] in the estimation of right-thinking members of society generally”1, “without justification or lawful excuse, [are] calculated to injure the reputation of another, by exposing him to hatred, contempt, or ridicule”2, or tend to make the claimant “be shunned and avoided and that without any moral discredit on [the claimant’s] part”3.

The burden of proving that the material is defamatory lies with the claimant. However, the claimant is not required to show that the material is false; there is a rebuttable presumption that this is the case and it is for the defendant to prove otherwise. In England and Wales, for an action to be successful, not only does the meaning of the material complained of have to be defamatory, the claimant must also show that it refers to him or her and that it has been communicated to a third party.

A defendant will be liable if the material meets the criteria above, and the defendant is the primary publisher of the material and does not succeed in establishing any of the defences in the Defamation Act 1952, namely:

Comment: Pedantic remark: the paragraph as stated is false. The Defamation Act 1952 (http://www.uk-legislation.hmso.gov.uk/RevisedStatutes/Acts/ukpga/1952/cukpga_19520066_en_1) modifies the way in which some of ... Reply?.

- justification i.e. that the material is true

3 Youssoupoff v MGM Pictures Ltd. (1934) 50 TLR 581, per Slesser LJ at 587

- fair comment, which protects statements of opinion or comment on matters of public interest

- absolute privilege, which guarantees immunity from liability in certain situations e.g. in parliamentary and court proceedings

- qualified privilege, which grants limited protection

on public policy grounds to statements in the media provided

that certain requirements are met; or

A defendant will also be liable if he or she is a secondary publisher and cannot use the defence contained in section 1 of the Defamation Act 1996. This provides that a defendant will not be liable where:

- he or she is not the author, editor or publisher of the statement complained of

- took reasonable care in relation to its publication, and

- did not know, and had no reason to believe, that what he did caused or contributed to the publication of a defamatory statement.

In addition, section 2 of the 1996 Act provides a procedure by which a defendant can make an offer of amends to enable valid claims to be settled without the need for court proceedings. Section 2 (4) provides that an offer to make amends is an offer to:

- make a suitable correction of the statement complained of and a sufficient apology to the aggrieved party,

- publish the correction and apology in a manner that is reasonable and practicable in the circumstances, and

- pay to the aggrieved party such compensation (if any), and such costs, as may be agreed or determined to be payable.

An offer of amends is not regarded as an admission of liability, and the offer may be withdrawn before it is accepted. However if an offer is accepted, under section 3 of the Act, the party accepting the offer may not bring or continue defamation proceedings in respect of the publication concerned against the person making the offer. If a case does go to court and the claimant succeeds, the court may award a range of remedies including damages and injunctions.

The multiple publication rule and the limitation period

Introduction

1. It is a longstanding principle of the civil law that each publication of defamatory material gives rise to a separate cause of action which is subject to its own limitation period (the “multiple publication rule”). The Law Commission considered the multiple publication rule in its 2002 scoping study “Defamation and the Internet” 4, and concluded that “There is a need to review the way in which the multiple publication rule interacts with the limitation period applying to archived material”. This paper therefore considers the operation of this rule and how any reform in this area might interact with the limitation period for defamation claims. It seeks views on the issues in principle. Should any change to the law be considered appropriate in the light of consultation responses, further consultation will take place on how this will operate in practice.

2. Issues in relation to the multiple publication rule have become more prominent in recent years as a result of the development of online archives. It is now common for organisations, particularly the media, and individuals to make previously published material available to everyone through an online archive. Whilst there is no statutory definition of what constitutes an online archive, for the purposes of this paper it should be taken to encompass electronic versions of traditional archives (such as those maintained by newspapers) as well as historical “blogs” (a type of online diary) and other electronic discussion forums.

3. The effect of the multiple publication rule in relation to online material is that each “hit” on a webpage creates a new publication, potentially giving rise to a separate cause of action, should it contain defamatory material. Each cause of action has its own limitation period that runs from the time at which the material is accessed. As a result, publishers are potentially liable for any defamatory material published by them and accessed via their online archive, however long after the initial publication the material is accessed, and whether or not proceedings have already been brought in relation to the initial publication.

[4] Law Commission, Defamation and the Internet: A Preliminary Investigation, Scoping Study No 2, December 2002

4. This is also the case with offline archive material (for example a library archive), but the accessibility of online archives means that the potential for claims is much greater in respect of material accessed online. However, it would not appear appropriate to restrict any reform to online archives alone as this could create confusion and unjustifiable differences in the law relating to online and offline material.

The current law

5. The multiple publication rule stems from the 19th century case of Duke of Brunswick v Harmer5, in which the Duke’s agent bought a back issue of a newspaper published 17 years earlier. The court held that this constituted a separate publication that was actionable in its own right. Under the Limitation Act 1980, each separate publication is subject to a limitation period of one year which runs from the time at which the material is accessed. This principle has been applied in a range of different cases, and was upheld in the context of internet publication by the House of Lords in Berezovsky v Michaels6. The rule was also upheld by the Court of Appeal in relation to archived material in Loutchansky v Times Newspapers Ltd7.

6. In Loutchansky, a Russian businessman brought two actions against The Times for libel. The first related to articles published in October 1999, which were subsequently placed on The Times’s online archive and were available for the public to access. The claimant brought a second action in December 2000 (more than one year after the original publication) in relation to the online archive. The Court of Appeal was asked to consider two issues in respect of the second action: the limitation period applicable to archives; and the nature of any privilege that should attach to them8.

7. On the issue of limitation the Court held that “it is a well established principle of English law that each individual publication of a libel gives rise to a separate cause of action, subject to its own limitation period.” This follows the authority from Duke of Brunswick v Harmer and subsequent cases. The Times argued that the English courts should follow the approach taken in the United States and recognise a single publication rule. The Court rejected this argument, holding that whilst archives had a “social utility”, it was a “comparatively insignificant aspect of freedom of expression.”9 It accepted that the notion of permitting actions based on fresh disseminations was “at odds with some of the reasons for the introduction of a 12 month limitation period”, but considered that any resulting damages were “likely to be modest.”10

footnotes: 5 [1849] 14 QB 185

6 [2000] 1 WLR 1004 7

[2002] 1 All ER 652 8 Qualified privilege grants limited protection on public policy grounds to statements in the media provided that certain requirements are met

6 [2000] 1 WLR 1004 7

[2002] 1 All ER 652 8 Qualified privilege grants limited protection on public policy grounds to statements in the media provided that certain requirements are met

8. On the second issue, whether privilege can attach to an online edition of a publication, the Court of Appeal held that as soon as The Times had become aware of the criticisms of the articles, and had not made any attempt to justify them, it should have drawn readers’ attention to the fact that their truth was disputed. Its failure to do so meant that it was not entitled to rely on any protection by way of privilege attaching to the original articles. However, the appeal was allowed as the Court decided that the initial High Court ruling misapplied the test in relation to qualified privilege for determining whether The Times was under a duty to publish the articles. The case was remitted back to the High Court, which held that The Times had not made out the defence of qualified privilege and found in the claimant’s favour.

9. The Times subsequently brought an application before the European Court of Human Rights alleging, inter alia, that the effect of the multiple publication rule breached its right to freedom of expression under Article 10 of the ECHR. The Court published its judgment in the case on 11 March 2009. It held unanimously that there was no violation of Article 10, because the Court of Appeal's finding that Times Newspapers had libelled the claimant by the continued publication on its internet site of two articles had not represented a disproportionate restriction on the newspaper's freedom of expression.

10. The Court observed that in the present case the two libel actions related to the same articles and both had been commenced within 15 months of the initial publication of the articles. The applicant's ability to defend itself effectively was not therefore hindered by the passage of time. Accordingly, the problems linked to ceaseless liability did not arise. However, the Court emphasised that while individuals who are defamed must have a real opportunity to defend their reputations, libel proceedings brought against a newspaper after too long a period might well give rise to a disproportionate interference with the freedom of the press under Article 10.

footnotes: 9 Ibid, at 676

10 Ibid

10 Ibid

Arguments for and against a multiple publication rule

11. In its scoping study, the Law Commission concluded that “the present [limitation] period of one year may cause hardship to claimants, who have little time to prepare a case. However, it is potentially unfair to defendants to allow actions to be brought against newspapers after their original publication, simply because copies have been placed in an archive. After a lapse of time, it may be extremely difficult to mount an effective defence, because records and witnesses are no longer available...Further consideration should be given to this issue, through the adoption of a US style single publication rule, or through a more specific defence that would apply to archives, whether held online or in more traditional libraries.”

12. There are several arguments that arise when considering whether the multiple publication rule should have a place in the modern law of defamation. When considering these, it is necessary to bear in mind the need to maintain a balance between freedom of expression and the right to a private life, which might be interfered with if an individual is not able to take action in respect of defamatory publications which damage his or her reputation.

13. One argument put forward for maintaining the multiple publication rule is that there is a limited likelihood of actions being brought in respect of archive material only; and that where a cause of action does arise, it seems unfair to deny a claimant the right to redress if they were to become aware of the publication of defamatory material through accessing archive material rather than the initial publication. However, there is also the counter-argument that such a rule creates potentially open-ended liability and therefore defeats the purpose of having a limitation period to protect defendants from extended liability.

14. There is also the view (expressed by the Court of Appeal) that archives are “stale news” and that therefore any injury to reputation will be minimal and damages awarded as a result will be small. However, it could be argued that material published in this way is not “stale” because the immediacy of access makes the impression much more lasting; and that it remains an important principle that a claimant should be able to defend their reputation, as the internet allows material to be instantly displayed, distributed and downloaded around the world many years after it was first published. On the other hand, if an action should arise, a defendant may have problems mounting a defence if a long period of time has elapsed and memories have faded or evidence has been destroyed.

15. In addition, there could be a risk that the operation of the multiple publication rule would result in multiple actions relating to the same material. However, the Law Commission’s scoping study indicated that claimant lawyers had expressed the view that where an action is brought in relation to defamatory material accessed on an archive, it is a relatively simple matter to place a notice on the archive, thus considerably lessening the impact of the defamation. Following from this, it may be argued that if the original material is the subject of defamation proceedings, the multiple publication rule neither produces a need for a blanket privilege attaching to archive material; nor unreasonably inhibits the maintenance of archives. If a warning notice were placed alongside the relevant archive material, this could reduce or remove the possibility of further proceedings being brought.

16. A further argument raised against the multiple publication rule is that it has the effect of obliging electronic service providers to police or monitor the content of archives for defamatory material, and that this is impracticable and possibly in breach of the E-Commerce Directive [Directive 2000/31/EC, OJ L178 p 1, 17 July 2000] , Article 15(1) of which prevents Member States from imposing on “information society service providers” a general obligation to monitor content. It is difficult to see how the multiple publication rule could effectively impose monitoring obligations in breach of Article 15(1), in particular given the protection from liability available to intermediary service providers by virtue of Regulations 17 to 19 of the E- Commerce Regulations. In any event, it is questionable whether any significant risk of actions being brought in respect of archive material exists and thus whether any real practical difficulties would arise.

17. The Court of Appeal in Loutchansky, while recognising the social utility of archives, took the view that they were a “comparatively insignificant aspect of freedom of expression” and were not harmed by the existence of the multiple publication rule. Against this, it may be argued that the rule does not adequately recognise the social importance of archives and that any operation of the rule in this context creates the danger that the dissemination of ideas and information over the internet will be inhibited, restricting freedom of expression.

Comment: I'm inclined to agree with the consultation's argument here, rather than the Court of Appeal's. Reply?.

Arguments for and against a single publication rule

18. A possible alternative to the multiple publication rule would be to adopt a single publication rule. This would mean that instead of the limitation period running from the time of each publication of the defamatory material, it would

run from the date of the first publication, even if copies of the material continued to be made and re-published years later. This would also mean that as regards defamation claims brought in England and Wales a claimant would be limited to bringing only one action in relation to particular defamatory material. It would prevent the bringing of multiple claims in the way that is possible at present. However, any such rule would not affect the possibility of a claimant suing abroad in respect of the publication of the same material in one or more foreign jurisdictions.

19. A single publication rule would provide clarity and prevent the possibility of open-ended liability. It would also remove some of the potential obstacles presented to defendants by the multiple publication rule, such as the possibility of having to mount a defence against an old claim. However, while there would be significant advantages for the defendant, a single publication rule could restrict the claimant’s ability to secure redress, particularly in situations where he or she was unaware of the original publication. This could be a significant disadvantage in respect of material published online as it would mean that if the claimant did not bring an action within the limitation period (for whatever reason), the defamatory material could remain accessible indefinitely. Even if a successful action was brought, it is possible that the defamatory material could remain in the public domain and the claimant could not bring a further action in respect of that material against the same publisher.

20. In these circumstances, a claimant may be further disadvantaged as there would no longer be any incentive on the host of defamatory material to remove or amend it, since there would be no risk of an action being brought against them. Currently, the failure to remove the material or attach a notice to it once the host became aware of it or its potentially defamatory nature would effectively lead to a new cause of action in respect of each ‘publication’12. This would cease to be the case should a single publication rule be adopted. One possible way of addressing this could be to provide that if material were found to be defamatory in one format (e.g. the print edition of a newspaper) then it would be obligatory for the material to be amended or removed where it was held in other formats under the control of the same publisher. Another option might be to provide that, where material is re-transmitted in a new format (i.e. a new article is written making use of a link to or a quotation from the original material) then any single publication rule would only protect the previous publisher and would not protect the publisher of the new article.

footnote: 12 See, Byrne v Deane [1937] 1 KB 818, 837-8 13

21. There is currently an obligation placed on the press13 and broadcast media14 to correct inaccurate and misleading material, which means that untrue defamatory material should be removed. However, adherence to the Press Complaints Commission (PCC) Code is purely voluntary, and although there is a statutory obligation on the broadcasting media, the internet is specifically excluded. This means that the controls to which ISPs are subject are entirely voluntary and codes of conduct apply only where the ISP signs up with an organisation such as ISPA15 or in situations where the PCC Code may apply. If a single publication rule were to be adopted it could therefore be necessary to consider whether there was a need to strengthen these provisions.

22. It would also be necessary to consider what would constitute a new publication. In relation to hard copy publications, in the United States it has been held that morning and afternoon editions of newspapers constitute separate publications16, as do hardback and paperback editions of a book.17 However, although the same previously published article appearing in the next edition of a monthly magazine will be a separate publication, the reprinting of a magazine edition in response to public demand does not constitute a new publication.18

23. In addition, there would be a need to consider whether online material that has been modified should be classified as a new publication. This issue was considered in relation to a website in the United States in Firth v State of New York19. This case concerned a report published at a press conference which was then placed on the internet the same day, but the claim was not filed for over a year. It was held that the limitation period ran from the time that the article was placed on the website, and that each “hit” on the website did not amount to a new publication. It was also held that unrelated modifications made to other parts of the site were irrelevant and did not create a new publication.

Comment: A sound ruling, I would suggest.

I'd further suggest that modifications to the same page that don't affect the content are similarly irrelevant and should not be considered a new publication. Reply?.

I'd further suggest that modifications to the same page that don't affect the content are similarly irrelevant and should not be considered a new publication. Reply?.

footnotes: 13 See, the Press Complaints Commission Code of Practice, http://www.pcc.org.uk/cop/practice.html, paragraph 1

14 Section 319 of the Communications Act 2003, through the Ofcom Broadcasting Code and the BBC producer’s guidelines

15 http://www.ispa.org.uk/about_us/page_16.html

16 Cook v Conners 1915 215 NY 175 ,br />17 Rinaldi v Viking Penguin, Inc (1981) 52 NY2d 422

18 Restatement (Second) of Torts, s 577A, illustrations 5 & 6

19 (2002) NY int 88

14 Section 319 of the Communications Act 2003, through the Ofcom Broadcasting Code and the BBC producer’s guidelines

15 http://www.ispa.org.uk/about_us/page_16.html

16 Cook v Conners 1915 215 NY 175 ,br />17 Rinaldi v Viking Penguin, Inc (1981) 52 NY2d 422

18 Restatement (Second) of Torts, s 577A, illustrations 5 & 6

19 (2002) NY int 88

24. The adoption of a single publication rule would also impact on material published offline as, if an action had already been brought in relation to

material published online, it may prevent further action being brought in relation to hard copy material. It would not appear appropriate for any change to apply only to online archives, as this could cause confusion and create unfairness, as the rights of claimants and defendants would differ according to the means by which the defamatory material was accessed. Any changes made to the law purely to take account of the issues arising from online archives could have undesirable consequences and affect areas of the law that currently operate without problems. The Government therefore believes that any change to the law to introduce a single publication rule would need to apply to all defamation proceedings.

Extending qualified privilege to material on online archives in certain circumstances

25. It has been suggested that rather than introduce a single publication rule, another possible approach would be to amend the Defamation Act 1996 to prevent actions in relation to publications on online archives outside the one year limitation period for the initial publication, unless the publisher refuses or neglects to update the electronic version, on request, with a reasonable letter or statement by the claimant by way of explanation or contradiction.

26. This would reflect the views expressed by the European Court of Human Rights in Times Newspapers v The UK, which recognised the important role played by online archives in preserving and making available news and information and acting as an accessible and free source for education and historical research, but emphasised the duty of those responsible for maintaining archives to ensure the accuracy of information contained therein. It would also reflect the earlier judgment of the Court of Appeal that the responsible maintenance of archives should lead to appropriate warnings or corrections being attached to potentially defamatory material.

27. This approach would require primary legislation, and could perhaps be addressed by an amendment to Section 15 of, and Schedule 1 to the Defamation Act 1996, which deals with the circumstances in which qualified privilege may attach to reports or statements on issues which are of public concern and the publication of which is for the public benefit. This could designate the publication of a report or other statement on an online archive as a statement which is privileged, subject to explanation or contradiction, where the material in question was first published more than one year ago.

28. Appropriate provisions would need to be drafted to ensure that qualified privilege did not extend to material which had remained on the archive despite having already been the subject of successful litigation, or to material which was the subject of ongoing litigation but an appropriate warning had not been posted on the archive.

29. The Government would welcome views on this suggested approach.

Q1 Taking into account the arguments set out above, do you consider in principle that the multiple publication rule should be retained? If not, should a single publication rule be introduced? Please give reasons for your answers.

Comment: Personally, I don't have any objection to the multiple publication rule, provided there is a sensible extension of qualified privilege. Certainly, I can see the rationale for it — repeating a libel or ... Reply?.

Q2 If the multiple publication rule were to be retained should there be an obligation to place a notice on an archive once the person responsible has been notified that the material is subject to defamation proceedings?

Q3 Do you agree that if a single publication rule were to be introduced, it should apply to all defamation proceedings, not just those relating to online publications?

Comment: I'm not convinced. Publication of a new book repeating old claims is fundamentally different from creating an online copy of a hard-copy publication — either shortly after the original publication or ... Reply?.

Q4 If a single publication rule were introduced,

a) should it be made obligatory to remove or amend material held in other formats under the control of the same publisher in the event of a successful defamation action against the original publication of the material?

b) should there be a provision that, where defamatory material is re- transmitted in a new format, the single publication rule would only protect the previous publisher and not the publisher of the new article?

Comment: If it can be proven that the publisher of the new article is aware of the original suit, perhaps. But the plaintiff should be required to notify the new publisher and provide them with an opportunity to ... Reply?.

c) if neither of these are considered appropriate, how could claimants’ interests be protected?

d) should the existing ‘voluntary’ obligations to correct inaccurate and misleading material be strengthened? If so, how should this be done? Please give reasons for your answers.

Q5 or a) if a single publication rule were introduced, do you consider that the approach taken in the United States in respect of what constitutes a new publication of hard copy material would be workable? If not, what changes should be made?

b) Should online content that has been modified be regarded as a new publication?

Comment: Only if the content itself has been substantially modified or if extraordinary attention has been drawn to the contentious content by the site owner.

Certainly, now that user-generated content ... Reply?.

Certainly, now that user-generated content ... Reply?.

c) Are there any other issues that would need to be resolved in establishing a single publication rule? Please give reasons for your answers.

Q6. As an alternative to introducing a single publication rule, do you consider that the Defamation Act 1996 should be amended to extend the defence of qualified privilege to publications on online archives outside the one year limitation period for the initial publication, unless the publisher refuses or neglects to update the electronic version, on request, with a reasonable letter or statement by the claimant by way of explanation or contradiction? Please give reasons for your answer.

Comment: Absolutely!

Online archives are the current equivalent of microfiche copies of newspapers. Most media organs, for example, publish online and leave the page there in perpetuity. The act of publication ... Reply?.

Online archives are the current equivalent of microfiche copies of newspapers. Most media organs, for example, publish online and leave the page there in perpetuity. The act of publication ... Reply?.

Interaction with the limitation period for defamation actions

Introduction

30. Consideration of the merits of altering the multiple publication rule should take into account the other rules governing the limitation period for defamation actions. Under section 4A of the Limitation Act 1980 (as amended by the Defamation Act 1996), the current limitation period for bringing an action for defamation or malicious falsehood is one year from the date on which the cause of action accrued (i.e. the date of publication of the allegedly defamatory material). Section 32A of the amended Act gives the court a discretionary power to disapply this time limit if it is equitable to do so.

31. In its 2001 report on Limitation of Actions20, the Law Commission recommended changing the limitation period for defamation actions to three years from the date of the claimant’s knowledge of the defamatory statement, with a long-stop period of 10 years from the date that the cause of action arose, whilst removing the discretion in section 32A of the 1980 Act. The Government intends to consult on draft legislation arising from the Commission’s report but considers that because of the link between the limitation period for defamation claims and issues relating to the multiple publication rule the two issues are best considered together in this paper.

Footnote: 20 Report No 270, http://www.lawcom.gov.uk/docs/lc270(2).pdf

32. Prior to the 1996 Act, the limitation period for defamation actions in England and Wales was three years from the date of publication. The rationale for the reduction to one year lay in the recommendations of the Supreme Court Procedure Committee chaired by Lord Justice Neill, which stated that reduction was warranted on account of “the general recognition that claims to protect one’s reputation ought to be pursued with vigour, especially in view of the ephemeral nature of most media publications.” The Committee further stated that the media considered that “the same reasoning would justify an even shorter period. Memories fade, journalists and their sources scatter and become, not infrequently, untraceable. Notes and other records are retained for only a short period, not least because of limitations on storage.”

33. The Committee suggested that it would only be in the most exceptional cases that a claimant could be justified in delaying bringing an action for more than a year. It took the view that the court should, for example, be sympathetic if the delay was caused by a genuine inhibition from suing, and that a judicial discretion to extend the period would be the answer for the very few claims that, with justification, were not started within a year. However, the Committee could not have anticipated the rapid advances in technology that have created the need for this consultation. With the advent of the internet, it is no longer accurate to say that most publications are ephemeral, as virtually any material is immediately and easily accessible for a potentially unlimited period. It is also no longer the case that storage is limited now that information can be easily stored on small disks, or indeed, online.

34. The Commission’s report on Limitation of Actions did not expressly consider the implications relating to the internet. Its 2002 Scoping Study looked again at the issue in that context and reiterated the case for the proposed increase in the limitation period. It argued that the current law combining the multiple publication rule with a short limitation period is disadvantageous for both claimants and defendants.

Options

35. A central aim of limitation periods is to balance the interests of potential defendants, who should not be expected to have the threat of proceedings hanging over them for a lengthy or indeterminate period, with the interests of claimants, who need time to establish and prepare their cases. A range of possible permutations exist in assessing the appropriate limitation period to adopt, depending on whether the multiple publication rule is retained or a single publication rule introduced. In the light of the Commission’s recommendation the following appear to be the main options available (although an intermediate period of two years would also be possible):

- One year from the date of publication with discretion to extend (i.e. the current position)

- Three years from the date of publication without discretion to extend

- Three years from the date of publication with discretion to extend

- One year from the date of knowledge of the publication without discretion to extend

- One year from the date of knowledge with discretion to extend

- One year from the date of knowledge with a 10 year long-stop from the date

of publication

- Three years from the date of knowledge of the publication without discretion to extend

- Three years from the date of knowledge with discretion to extend

- Three years from the date of knowledge with a 10 year long-stop from the date of publication (as proposed by Law Commission)

Key issues for consideration

Date of publication or date of knowledge

36. There are a number of key issues which are relevant when considering the merits of these options. The first of these is whether the limitation period should run from the date of publication of the allegedly defamatory material or the date the claimant becomes aware (or could reasonably be expected to become aware) that a cause of action exists (the “date of knowledge”). Using the date of knowledge could be fairer to claimants as time would not start to run until they know, or could reasonably be expected to know, of the existence of the facts that form the basis for the action. This would mean that claimants would not potentially find themselves barred from bringing an action before they have become aware of the allegedly defamatory material. In the event that the multiple publication rule were abolished, this would go some way towards reducing any disadvantage to claimants arising from the adoption of a single publication rule.

37. However, there could be significant disadvantages if the limitation period were to run from the date of knowledge, as the length of time for which the defendant is potentially vulnerable to claims could be substantially greater, and more difficult to ascertain, than if a ‘date of publication’ approach is used. Although in practice in most cases the date of knowledge would be unlikely to differ substantially from the date of publication, in some instances it could create uncertainty and potentially open-ended liability. This could lead to evidential difficulties if the claimant only became aware of the allegedly defamatory material some time after its publication. It could also create a risk of longer and more complex litigation where there was a dispute over exactly when the claimant became or should have become aware of the material.

38. Retaining the current approach of using the date of publication would give greater certainty and avoid any possible evidential problems and disputes over the date of knowledge. In the event that the multiple publication rule is retained, the resulting benefits for claimants would appear to negate the need to safeguard further claimants’ position by moving to a ‘date of knowledge’ approach. However, if a single publication rule were to be adopted, a date of publication approach could mean that claimants may find themselves barred from bringing an action before they have become aware of the allegedly defamatory material, without any possibility of an action if the material were on an archive.

The need for a discretion

39. As noted above, section 32A of the Limitation Act 1980 currently gives the court a discretion to extend the limitation period where it is equitable to do so. When deciding whether to exercise this power, the court is required to have regard to the length of, and reasons for, the delay on the part of the claimant. Where the delay was due to the claimant being unaware of all or any of the facts that are essential to the cause of action, it is relevant to consider the date on which the facts became known to him and whether in the circumstances he acted promptly and reasonably once he knew that he might have a cause of action. Regard should also be had to the likely unavailability or lack of cogency of evidence by virtue of the action having been brought beyond the normal limitation period. Examples of instances where extensions have been respectively denied and allowed are the cases of Steedman and Others v British Broadcasting Corporation21 and Wood v West Midlands Police.22

footnote: 21 Steedman & Ors v British Broadcasting Corporation [2001] EWCA Civ 1534

22 Wood v West Midlands Police [2004] EWCA Civ 1638

22 Wood v West Midlands Police [2004] EWCA Civ 1638

40. If a ‘date of publication’ approach were retained with either a multiple publication rule or a single publication rule, it would appear appropriate for the court to continue to have a discretion to allow claims outside the limitation period. If a single publication rule were adopted, this could go some way to remedy the difficulty mentioned above of claimants finding themselves barred from bringing an action before they have become aware of the allegedly defamatory material. It could be argued that a discretion would provide an effective means of ensuring that claims could proceed where it was reasonable to do so, and that claimants would not be significantly disadvantaged should the multiple publication rule cease to exist. On the other hand, the discretion in section 32A has been used sparingly in exceptional circumstances, and it could be argued that it would not provide sufficient protection to claimants in the absence of the multiple publication rule.

41. If it were decided that the limitation period should run from the date of knowledge, it would not appear appropriate for there to be a discretion as well, as this would be likely to compound any uncertainty and potential difficulties for defendants which might arise from the date of knowledge.

Length of limitation period

42. Another issue for consideration is whether the limitation period should remain at one year or be extended to three years from either the date of knowledge, as recommended by the Commission, or the date of publication (or to the intermediate period of two years).

43. Arguments in favour of retaining the one year period include the fact that the burden currently rests on the defendant to prove that the publication of the allegedly defamatory material is justified, and that a long limitation period could cause difficulties in producing evidence to do this. On the other hand, the Commission expressed concern that a one year period may not give claimants sufficient time to prepare a claim properly. In addition, it considered that it would be desirable to remove the anomalies between the limitation period in England and Wales and that in Scotland (which currently has a limitation period of three years from the date of knowledge) and between the limitation period for defamation and that for malicious falsehood or negligent misstatement.

44. The Commission took the view that on balance a limitation period of three years from the date of knowledge would be appropriate. However, the one year period has now been in operation for several years and does not appear to have caused significant difficulties. As noted above, the section 32A discretion gives some flexibility where the court considers it just for the period to be waived. In addition, we are not aware of any evidence that the difference in the limitation period between England and Wales and Scotland has in practice caused any problems. In the event that the multiple publication rule is retained, there would not therefore appear to be any strong justification for changing the limitation period from one year from the date of publication.

45. If a single publication rule were adopted, it may be considered that a longer limitation period from either the date of publication or the date of knowledge would help to offset any potential disadvantage to claimants. However, a longer period would be likely to increase the potential for evidential difficulties and disputes. This would be exacerbated if a ‘date of knowledge’ approach were used because ‘knowledge’ may only occur some time after publication. Also, in the absence of any evidence that the current one year period is causing significant problems, it is unclear what benefit a longer period would in itself provide.

The need for a long-stop period

46. The Commission’s proposal to prevent defendants being subjected to a potentially open-ended liability where the limitation period runs from the date of knowledge was to have an additional ten year long-stop period that would run from the date of publication. This would have the advantage of providing some degree of certainty for defendants without significantly disadvantaging claimants. However, the period within which potential actions could be brought would still be a long one.

47. The Commission noted in its 2002 scoping study that “although the long-stop would fit well with a single publication rule, it is ineffective when combined with the present “multiplication rule”, because it would start to run each time material was downloaded”. A long-stop would clearly also not be relevant where a date of publication approach is used.

Conclusion

48. In the light of the arguments discussed above and in the absence of evidence of hardship or difficulties with the present law, the Government considers that if the multiple publication rule were retained, the limitation period should not be extended from the current period of one year from the date of publication (with discretion to extend). If a single publication rule were to be introduced, the Government considers that the arguments for extending the limitation period beyond one year are not strong. However, the questions of whether a ‘date of publication’ or ‘date of knowledge’ approach should be used, and whether the latter should be accompanied by a ten year long-stop from the date of publication, appear more finely balanced.

Q7 Do you agree that if the multiple publication rule is retained, the limitation period should remain at one year from the date of publication (with discretion to extend)? If not, what limitation period would be appropriate and why?

a) If a single publication rule were introduced, should the limitation period of one year run from the date of publication (with discretion to extend) or the date of knowledge (without discretion to extend)? If the latter, should there also be a ten year long-stop from the date of publication?

b) If you consider that an alternative approach would be appropriate, what should this be and why?

Questionnaire

We would welcome responses to the following questions set out in this consultation paper.

1. Taking into account the arguments set out above, do you consider in principle that the multiple publication rule should be retained? If not, should a single publication rule be introduced? Please give reasons for your answers.

2. If the multiple publication rule were to be retained should there be an obligation to place a notice on an archive once the person responsible has been notified that the material is subject to defamation proceedings?

3. Do you agree that if a single publication rule were to be introduced, it should apply to all defamation proceedings, not just those relating to online publications?

4. If a single publication rule were introduced,

a) should it be made obligatory to remove or amend material held in other formats under the control of the same publisher in the event of a successful defamation action against the original publication of the material?

b) should there be a provision that, where defamatory material is re- transmitted in a new format, the single publication rule would only protect the previous publisher and not the publisher of the new article?

c) if neither of these are considered appropriate, how could claimants’ interests be protected?

d) should the existing ‘voluntary’ obligations to correct inaccurate and misleading material be strengthened? If so, how should this be done? Please give reasons for your answers.

5. a) If a single publication rule were introduced, do you consider that the approach taken in the United States in respect of what constitutes a new publication of hard copy material would be workable? If not, what changes should be made?

b) Should online content that has been modified be regarded as a new publication?

c) Are there any other issues that would need to be resolved in establishing a single publication rule? Please give reasons for your answers.

6. As an alternative to introducing a single publication rule, do you consider that the Defamation Act 1996 should be amended to extend the defence of qualified privilege to publications on online archives outside the one year limitation period for the initial publication, unless the publisher refuses or neglects to update the electronic version, on request, with a reasonable letter or statement by the claimant by way of explanation or contradiction? Please give reasons for your answer.

7. Do you agree that if the multiple publication rule is retained, the limitation period should remain at one year from the date of publication (with discretion to extend)? If not, what limitation period would be appropriate and why?

8. a) If a single publication rule were introduced, should the limitation period of one year run from the date of publication (with discretion to extend) or the date of knowledge (without discretion to extend)? If the latter, should there also be a ten year long-stop from the date of publication?

b) If you consider that an alternative approach would be appropriate, what should this be and why?

Appendixes

Extra copies

Further paper copies of this consultation can be obtained from this address and it is also available on-line at www.justice.gov.uk

Alternative format versions of this publication can be requested from: Tel: 020 3334 3220 Email: defamationandtheinternet@justice.gsi.gov.uk

Publication of response

A paper summarising the responses to this consultation will be published in March 2010. The response paper will be available on-line at www.justice.gov.uk/consultations/consultations.htm

Cost Benefit Analysis

3.1 This section sets out some potential costs and benefits of various options under consideration in relation to the multiple publication rule and associated limitation periods.

BASE CASE (“do nothing”) Description

3.2 The Impact Assessment and HMT Treasury Green Book Guidance requires that all options are assessed relative to a common ‘base case’ over the appropriate period of relevant ‘do-something’ options. The base case for this IA has been assumed to be no change to the law, that is to say, to retain the existing multiple publication rule and the existing limitation period of one year from the date of publication (with discretion to extend).

3.3 Making no change would mean that people who were the subject of defamatory material in an online archive could continue to bring a defamation claim at any point when that material is accessed. However, it would also mean that companies operating online archives would be subject to potentially open-ended liability, which could be said to defeat the purpose of the limitation period.

3.4 As the number of Internet users increase and with it the plethora of online publishers with more complex archives, the potential for published defamatory material still to remain accessible by many people will increase. This is likely to lead to more complaints to online publishers over time, with the potential for such publishers increasingly becoming more prone to not publishing certain types of information.

OPTION 1

Description

3.5 To introduce a single publication rule but retain the existing limitation period of one year from the date of publication (with discretion to extend), so that only one claim could be brought in respect of the same defamatory material.

3.6 With respect to the base case (“do-nothing”), Option 1 would lead to costs and benefits only associated with the change from a multiple to a single publication rule.

Costs of Option 1

Claimants

3.7 Option 1 would impose costs on claimants in the future, as it would leave them without an adequate legal protection for taking legal action against defamatory material republished or accessed at any time after the expiry of the initial limitation period, and they would be unable to take action to protect their reputation in these circumstances. It would also leave them with no recourse should they not find out about the initial defamatory publication until after the expiration of the limitation period. The costs although personal could in many instances impact on their private businesses and long term careers, with significant future earnings foregone.

3.8 Option 1 may provide a greater incentive, relative to the base case (or current position), to web publishers to publish material on their archives than at present. The number of instances of defamatory material being published may therefore go up, effectively raising the personal costs to claimants, who would not be able to have recourse to the courts. In the light of the increase in publishers maintaining online archives and the likelihood of more defamation disputes these costs could be substantial.

Benefits of Option 1

3.9 Option 1 may lead to benefits for web publishers, the justice system and wider society.

Web Publishers

3.10 The likely benefits to web publishers from the change from a multiple to a single publication rule may include :

3.11 Resource cost savings – web publishers would no longer have to invest time and effort to monitor archives and deal with complaints related to potentially defamatory material once the one year limitation period for that material has ended.

- Legal proceeding costs – there would be no further legal risk associated with publication of material from archives.

- Reduced “preventative costs” – Online publishers may take steps to ensure material posted in their archives is not likely to be defamatory (this may include measures such as a re-edit before publishing in an online archive). Putting these processes in place may entail costs. In so far as Option 1 amends the open ended nature of the liability on web publishers, it would lead to reduced “preventative costs”.

Justice System

3.12 There would be some benefits to the Justice System from introduction of Option 1. Although this is likely to be minimal based on historic trends, the costs of defamation cases can be high and time consuming. In addition, relative to the base case of rising internet usage, the actual savings to the Justice System over time may be significantly larger than at present.

Wider Society

3.13 There are likely to be wider benefits to society from Option 1, principally from the reduced “chilling effect”. As discussed above, the current legal position of multiple publication may have the unintended consequence of reducing freedom of expression as web publishers consider the expected costs too great to publish certain stories that may make their way inevitably into archives. In so far as Option 1 reduces these expected costs, this would enhance greater freedom of expression from web publishers, albeit not without other costs as discussed above.

OPTION 2

Description

3.14 To introduce a single publication rule and amend the limitation period to run for one year from the date of knowledge (without discretion to extend), so that only one claim could be brought in respect of the same defamatory material, but the time limit for bringing the claim would depend on the claimant’s knowledge of the material rather than the date it was published.

3.15 With respect to the base case “do-nothing”, Option 2 would lead to costs and benefits from the change from a multiple to a single publication rule, and from moving the limitation period from one year from the date of publication to one year from the date of knowledge.

Costs of Option 2

Claimants

3.16 Same as Option 1 for impacts related to change from multiple to “single publication rule”. However, Option 2 costs are likely to be broadly lower due to changes in the limitation period which allows claimants one year from the date of knowledge to lodge a defamation claim. It also would prevent them from being barred from making a claim in situations where they had been unaware of the existence of the allegedly defamatory material until more than one year from the date of publication.

Justice System

3.17 The ambiguity caused by the alteration of the limitation period to “one year from the date of knowledge” could lead to an increase in court proceedings due to arguments over when a claimant could reasonably have been expected to have “knowledge” of the existence of defamatory material.

Benefits of Option 2

3.18 Option 2 may lead to benefits for web publishers, the justice system and wider society.

Web Publishers

3.19 Same as Option 1 for impacts relating to a change from the multiple publication rule to a “single publication rule”. However, under Option 2 the benefits to web publishers are likely to be broadly lower due to the changes in the limitation period (to one year from the date of knowledge) which would reduce the certainty over the extent of the liability for publishers.

Justice System

3.20 Same as Option 1 for impacts related to change from multiple to “single publication rule”. However, Option 2 benefits to the justice system are likely to be broadly lower due to increased probability that more claimants may be able to pursue claims through the courts due to the changes in the limitation provision.

Wider Society

3.21 Same as Option 1 for impacts related to the change from multiple to “single publication rule”. However, Option 2 benefits for wider society from a reduced chilling effect is likely to be broadly lower. The incentives for publishers to be cautious would be stronger under Option 2 than Option 1.

OPTION 3

Description

3.22 To amend the Defamation Act 1996 to prevent actions in relation to publications in online archives outside the one year limitation period for the initial publication, unless the publisher refuses to update the electronic version, on request, with a reasonable letter or statement by the claimant, so that claims outside the limitation period would only be possible in these circumstances.

3.23 This means that legal action could normally only be taken by claimants within one year from the time a defamatory article is first published. Defamatory publications thereafter (i.e. from archive sources) could only be the subject of a legal action if, upon request, the first time publisher refuses to update the archive with a statement or letter from the claimant explaining or contradicting the original article.

3.24 With respect to the base case “do-nothing”, the only change relevant for analysis under Option 3 is the costs and benefits associated with removing liability from archive sources where statements or letters from claimant explaining or contradicting the original article are published.

Costs of Option 3

3.25 Option 3 may lead to potential costs for claimants and web publishers.

Claimants

3.26 Option 3 would impose costs on claimants in the future, because although it maintains conditional liability on web publishers it does not prevent the reputation of the claimant from suffering by having defamatory information in the public domain. In addition, the Option places a burden on claimants to write to the publisher and monitor that the publisher has updated the material in the archive. This has resource implications for the individual and may be deemed unfair to claimants.

3.27 In addition, the presence of this material on archives makes it more likely that other publishers would cite such information and the qualifications to it may become less apparent in those future citations. Therefore the information may have a wider “ripple effect”, although the primary online archive itself would have the claimant’s account of the correct position.

Web Publishers

3.28 There could be an administrative cost to operators of online archives of amending the archive where an update is requested. However, these costs are likely to be minimal.

Benefits of Option 3

3.29 Option 3 may lead to benefits for web publishers, the justice system and wider society.

Web Publishers

3.30 The likely benefits to web publishers from retaining the online archive publications subject to allowing claimants to publish their views are similar as those set out under Option 1.

Justice System

3.31 Same as Option 1.

Wider Society

3.32 Same as Option 1

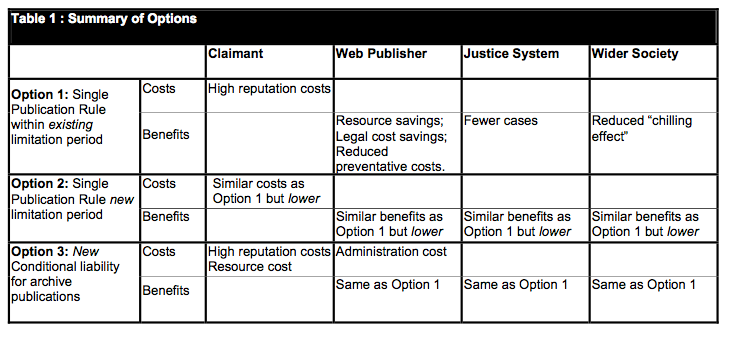

Summary of Options

3.33 Table 1 presents a high level summary of costs and benefits across the three options focused on the key affected areas:

NB: This is a high level summary to give some indicative impacts. The actual impacts, discussed in the main narrative are likely to be more varied.

Question 9

How many defamation cases have you been involved in each of the last three years in which the multiple publication rule has been an issue? What was the outcome ?

Question 10

What costs have you incurred over this period in monitoring archives specifically in relation to defamatory material?

Question 11

Do you agree with the benefits identified for each option? Are there any others that you consider would arise?

Question 12

a) Do you agree with the costs identified for each option? Are there any others that you consider would arise?

b) Are you able to quantify any of the costs involved? If so, please provide the relevant figures.

4. Competition Assessment

4.1 The markets affected by these proposals are the media, publishing and internet service industries. None of the options under consideration would have a negative effect on competition. However, the impact of certain options would be more positive than others. Further consideration will be given to developing a formal competition assessment during the consultation process and in the light of responses to consultation in preparation for further consultation on any proposals being taken forward.

Question 13

Do you have any comments on competition issues that should be taken into account in considering these proposals further? Please give details.

5. Small Firms Impact Assessment

5.1 The Impact Assessment Guidance states that “any new proposal that imposes or reduces the cost on business requires a Small Firms Impact Assessment Test”. The assessment of the potential impacts of reforming the liability on ISPs has relied on the BERR Small Firms Impact Assessment Guidance (September 2007). It is unclear at this stage what the impact on firms might be. We will be contacting a number of small businesses during the consultation process to seek further information on any particular impacts to small firms and the likely costs and effects to their business.

Question 14

What would be the potential costs/savings to your business of the options under consideration? Please explain how these costs or savings will arise, indicate the size of your business: micro (1-9), small (10-49), medium (50-250) and also which sector you operate in.

6. Legal Aid and Justice Impact Test

6.1 At present, legal aid is not available for defamation actions except in exceptional circumstances where Ministers may grant funding in individual cases subject to specific criteria being met. Such cases are such a rarity that any costs incurred to the legal aid fund are likely to be regarded as de minimis. Certain of the options may have implications for the courts, although it is not expected that these would be substantial. Further consideration will be given to any potential impact during the consultation period and in light of the responses to consultation.

7. Race, Disability and Gender Assessment

7.1 The proposals have been screened for impact on equalities. On the evidence available, we do not consider that any of the options impact differentially on individuals or groups within the population according to their ethnicity, religion, disability, age, gender or sexual orientation. However, we have no information on whether any of these groups are more likely to be involved in defamation proceedings, which could affect our assessment.

Question 15

Do you agree with our initial view that none of the options under consideration will have any equality impacts? If not, please explain your reasons.

8. Human Rights

8.1 The multiple publication rule was recently considered by the European Court of Human Rights in the case of Times Newspapers v The United Kingdom. The Court held unanimously that there was no violation of Article 10. The Court observed that in the case before it the two libel actions related to the same articles and both had been commenced within 15 months of the initial publication of the articles. The applicant's ability to defend itself effectively was not therefore hindered by the passage of time. Accordingly, the problems linked to ceaseless liability did not arise. However, the Court emphasised that while individuals who are defamed must have a real opportunity to defend their reputations, libel proceedings brought against a newspaper after too long a period might well give rise to a disproportionate interference with the freedom of the press under Article 10.

The consultation criteria

The seven consultation criteria are as follows:

When to consult – Formal consultations should take place at a stage where there is scope to influence the policy outcome.

Duration of consultation exercises – Consultations should normally last for at least 12 weeks with consideration given to longer timescales where feasible and sensible.

Clarity of scope and impact – Consultation documents should be clear about the consultation process, what is being proposed, the scope to influence and the expected costs and benefits of the proposals.

Accessibility of consultation exercises – Consultation exercises should be designed to be accessible to, and clearly targeted at, those people the exercise is intended to reach.

The burden of consultation – Keeping the burden of consultation to a minimum is essential if consultations are to be effective and if consultees’ buy-in to the process is to be obtained.

Responsiveness of consultation exercises – Consultation responses should be analysed carefully and clear feedback should be provided to participants following the consultation.

Capacity to consult – Officials running consultations should seek guidance in how to run an effective consultation exercise and share what they have learned from the experience.

These criteria must be reproduced within all consultation documents.

Defamation and the internet: the multiple publication rule Consultation Paper

Consultation Co-ordinator contact details

If you have any complaints or comments about the consultation process rather than about the topic covered by this paper, you should contact Julia Bradford, Ministry of Justice Consultation Co-ordinator, on 020 3334 4492, or email her at consultation@justice.gsi.gov.uk.

Alternatively, you may wish to write to the address below:

Julia Bradford Consultation Co-ordinator Ministry of Justice 102 Petty France London SW1H 9AJ

If your complaints or comments refer to the topic covered by this paper rather than the consultation process, please direct them to the contact given under the How to respond section of this paper at page 30

© Crown copyright Produced by the Ministry of Justice

Alternative format versions of this report are available on request from 020 3334 3220.